Last Post: Devout Christian Woman,

.

I am a Shawnee.

My forefathers were warriors.

Their son is a warrior.

Tecumseh

Warrior Son

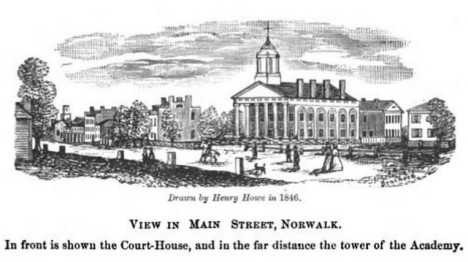

May of 1810 was momentous for David Gibbs of Norwalk, Connecticut: he passed the Connecticut bar and married Elizabeth Lockwood a lifelong resident of that town and daughter of Stephen Lockwood, a Sufferer, who had lost his possessions in the Battle of Norwalk over thirty years before. [1]

Although Stephen had been granted land in the Fire Lands, it had been only two years before that the Fire Lands of northern Ohio, set aside for the Sufferers had been surveyed and he was finally assigned his portion. [2]

Charles Robert Sherman

The Ohio frontier was still a dangerous place for settlers, with frequent warfare with Native American tribes. But despite the danger, David decided to scout out his father-in-law’s land. The question was, whom should he ask to accompany him. His good friend, Charles Robert Sherman was an obvious choice. [3]

Charles Sherman was born and raised in Norwalk. Like David, in the spring of 1810 he had also passed the bar and married a Norwalk woman: Mary Hoyt. The two men had other similarities in their life histories: they were born within a few months of each other, had studied law together – and both had a personal interest in the Firelands of northwestern Ohio.

David’s father-in-law, Robert Lockwood’s home and business had been burned by the British during the Battle of Norwalk in the American Revolution. This made him one of the “Sufferers,” eligible for a portion of land in the Firelands. That land had been surveyed in 1808, and Robert had been assigned his portion in what are now Sherman and Norwalk Townships of Huron County. [2]

Charles was born in Norwalk, in on September 26, 1788 to Taylor and Elizabeth Stoddard Sherman. His father was a lawyer, and Charles studied law under his tutelage and that of a Judge Newman of Newtown, Connecticut. Taylor was not a Sufferer, but while a trustee of the Connecticut Land Company, had purchased land in Sherman Township, which was named after him. [4]

The two friends departed Norwalk, Connecticut that summer and headed for the Firelands of Ohio. [3] However, in route, they had a change of plans. The Native American chief, Tecumseh, was threatening the frontier, a lead in to Tecumseh’s War, [4] so they diverted to Lancaster, near Columbus. Charles decided to settle there, and after acquiring land and building a cabin, returned for his bride. [5]

David did not settle in Lancaster with his friend. He returned to Connecticut and took advantage of an opportunity in Bridgeport, where he practiced law for two years. Then came the War of 1812. He enlisted in David Captain Tilden’s Company, 37th U.S. Infantry at Fort Griswold, New Jersey on April 30, 1813, and was discharged on May 17, 1815. Apparently, he saw no action. [6]

At the conclusion of the war, danger from Native American’s had been removed and the frontier was open for settlement. David decided to visit the Firelands again, this time with his father-in-law and brother-in-law. That trip will be the subject of my next series of posts.

Footnotes

[1] The evening of July 10, 1779, British troops under the command of Brigadier General William Tyron landed at the mouth of the Norwalk River. The following morning, the troops moved up the river toward Norwalk, burning everything in their path. By the end of the “battle” eighty houses, two churches, eighty-seven barns, seventeen shops, and four mills had been destroyed worth an estimated 26 thousand British pounds (See the Wikipedia article Battle of Norwalk and W.W. Williams, History of the Fire-Lands, Comprising Huron and Erie Counties, Ohio, With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of the Prominent Men and Pioneers; Leader Printing Company, Cleveland, Ohio; 1879, p 14. and Erie Mesnard, “Surveys of the Fire Lands, so called being a part of the Western Reserve, sometimes called New Connecticut,” The Firelands Pioneer, Old Series, Volume V; The Firelands Historical Society, June 1864; p 94.).

In 1792, the Connecticut General Assembly authorized compensation of over one-hundred sixty-one thousand pounds (New England currency) to about eighteen hundred seventy “Sufferers.” David Gibbs father-in-law Stephen Lockwood’s share was set at 18 pounds, 12 shillings (WW Williams, pp. 15-16).

[2] The Firelands was first surveyed in 1806, however, the results were challenged and deemed flawed. Another survey was required and was completed in 1808. A final apportionment to the “Sufferers” took place by lottery in November of that year. (WW Williams, pp. 23-25.) Stephen Lockwood was allotted land in Sherman and Norwalk townships. (WW Williams pp. 112, 284.)

[3] “David Gibbs,” Obituaries: The Firelands Pioneer, New Series, Volume IX; The Firelands Historical Society; 1896; page 542 and “Incidents in the Life of Elizabeth Lockwood Gibbs,” The Firelands Pioneer, Old Series, Vol XI, October 1874, page 83.

[4] See Wikipedia articles for Taylor Sherman and Charles Robert Sherman, Also, “Charles Robert Sherman on the website: “Former Justices of the Ohio Supreme Court.” An account of the naming of Sherman Township is in Baughman, A.J., History of Huron County Ohio: Its Progress and Development, Volume I, The S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, Chicago, IL, 1909; p. 284

[5] The Shawnee Chief Tecumseh was a thorn in the side of Americans for many years as leader of a large multi-tribe confederacy based out of “Prophetsville” in Indiana. In August of 1810, he appeared with a group of warriors at General Henry Harrison’s headquarters in Vincennes with a list of demands, which the General immediately rejected. The situation quickly deteriorated and open warfare was narrowly averted by another Native American Chief. Tecumseh departed, threatening war. See the Wikipedia article Tecumseh.

News of this encounter terrified settlers on the frontier and caused many who were about to push into newly opened territories such as the Firelands to revise their plans, to include David Gibbs and his friend Charles Sherman.

Shawnee Chief Tecumseh and William Tecumseh Sherman

Although Tecumseh foiled Charles Sherman’s plans to settle on his father’s land in the Firelands, he was impressed by the man’s skill as a warrior. Charles remembered him through the years, and when Charles and Mary christened their sixth child in 1820, they named him after the Chief. That child also became a renowned warrior. His name was William Tecumseh Sherman.

[6] “David Gibbs,” Obituaries: The Firelands Pioneer, New Series, Volume IX; The Firelands Historical Society; 1896; page 542; William A. Gordon, A compilation of registers of the Army of the United States, from 1815 to 1837, inclusive. To which is appended a list of officers on whom brevets were conferred by the President of the United States, for gallant conduct or meritorious services during the war with Great Britain, James C. Dunn, Printer, 1837, page 38; and War of 1812 Pension Applications. Washington D.C.: National Archives. NARA Microfilm Publication M313, 102 rolls.

#

This is the second of a series of posts about the Lockwood and Gibbs families trek to the Firelands in 1816.

#

Thanks for visiting! Share and like this post below, and on Facebook. Let me know what you think in the comments. I’d love to hear from you!

Filed under: Frontier Life, Gibbs, Lockwood, Native American, Uncategorized | Tagged: Battle of Norwalk, Charles Sherman, David Gibbs, Firelands History, Norwalk CT, Ohio History, Stephen Lockwood, Sufferers' Land History, Taylor Sherman, Tecumseh, William Henry Harrison, William Tecumseh Sherman | 5 Comments »

Two years after establishing the Norwalk Reporter, the same year his daughter married Jonas Benedict, Henry, along with Platt Benedict and several other investors, founded The Norwalk Manufacturing Company to produce flour, paper and other commodities. The company built a factory on Medina Road. It was the first enterprise of its kind west of the Alleghenies. The company had problems from the beginning and was never a financial success. Soon after incorporation, all investors except Henry, Platt and one other man pulled out of the venture. [3]

Two years after establishing the Norwalk Reporter, the same year his daughter married Jonas Benedict, Henry, along with Platt Benedict and several other investors, founded The Norwalk Manufacturing Company to produce flour, paper and other commodities. The company built a factory on Medina Road. It was the first enterprise of its kind west of the Alleghenies. The company had problems from the beginning and was never a financial success. Soon after incorporation, all investors except Henry, Platt and one other man pulled out of the venture. [3] When she arrived at her friend Fanny Benedict’s house, she learned that young Platt had come downstairs early in the morning and stood by the fireplace to get warm. An ember landed on the boy’s nightgown, catching it on fire and burning him badly. Fanny and Jonas were in terrible shock from the sight of their son running through the house engulfed in flames.

When she arrived at her friend Fanny Benedict’s house, she learned that young Platt had come downstairs early in the morning and stood by the fireplace to get warm. An ember landed on the boy’s nightgown, catching it on fire and burning him badly. Fanny and Jonas were in terrible shock from the sight of their son running through the house engulfed in flames.