Sufferers’ Land

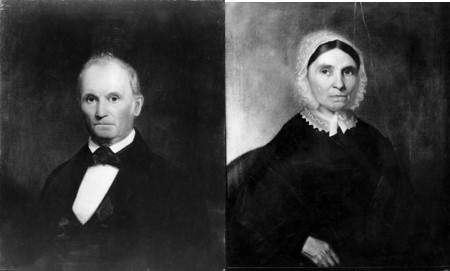

The Wickham Family in the 1850’s

by Dave Barton

In 1850, the Wickham household on East Main was bulging at the seams with fourteen people living under its roof. Fredrick and Lucy now had seven children: Charles, age thirteen; Catharine, eleven; William, nine; Fredrick, seven; Mary, five; Sarah, three; and the baby, one-year-old Lucy. Also living in the house were Lucy’s brother Charles Preston, their father Samuel Preston, age seventy-two, and their grandfather Timothy Taylor who was ninety-five.

The Wickham home today. Now located on Case Avenue, it is the museum of the Firelands Historical Society

Lucy was a devoted Presbyterian. She insisted that her children attend Sunday school and that they went properly attired. They each carried two handkerchiefs, one a “shower” and the other a “blower.”

Frederick, who had grown up an Episcopalian, never attended church with the rest of his family, but went to the Universalist Church across the street. He could not accept the Presbyterian doctrine of predestination and damnation. As he explained, he “could not condemn one of his children to Hell, and he didn’t believe the Lord could either.” [1]

Henry Buckingham, son of George Buckingham, also lived with the Wickhams and worked at the newspaper. Like Caroline Benedict, Lucy had help taking care of her family, two German women, Julia Berbach, age twenty-two, and Teresa Beecher, age eighteen. [2]

Running such a large household was undoubtedly a great burden for Lucy. In addition to rearing seven children, she had to care for her brother, father, and grandfather. By 1850, her grandfather, “Grandsire” Timothy Taylor, had lived a long eventful life, serving as a soldier in the Revolution, raising a family and moving west at an advanced age to start a new life on the frontier.

In spite of his age, Grandsire Taylor still possessed clear and sound judgment, and his mental faculties were unimpaired. He was universally esteemed by his neighbors and acquaintances for the integrity of his character, for the kindness of his heart, and for the sociability and cheerfulness which enlivened his intercourse with all, during his long and useful life of almost a century.

However, Grandsire Taylor could not live forever. He died in his bed at Lucy’s home on Wednesday, February 26, 1851, at the age of ninety-seven. [3]

The following year there were two more deaths, one each in the Wickham and the Benedict households. Although the death at the Benedict home was expected, the one at the Wickham home was an unforeseen tragedy.

Footnotes:

[1] These stories about Frederick & Lucy’s religious beliefs are from undated notes by Harriott Wickham Barton in the possession of the author.

[2] Information about Frederick & Lucy’s household is from The 1850 Huron County Census, page number 1b

[3] From the obituary of Timothy Taylor in The Firelands Pioneer, New Series, Volume XX; The Firelands Historical Society; December 1918; pp. 2196-7.

#

This post was first published on this blog in 2009.

#

Previous Post: The Benedict Family in the 1850’s

Next Post: End of an Era

#

Thanks for visiting! Share and like this post below, and on Facebook. Let me know what you think in the comments. I’d love to hear from you!

Filed under: Benedict, Buckingham, Taylor, Uncategorized, Wickham | Tagged: Buckingham Genealogy, Firelands History, Firelands Museum Norwalk Ohio, Frederick Wickham, Henry Buckingham, Lucy Wickham, Norwalk Ohio History, Ohio History, Presbyterian Church, Sufferers' Land History, timothy taylor, U.S. Census 1850, Universalist Church | 8 Comments »

ck Sunday morning, Henry woke to cries of alarm. A fire at the factory! Volunteers hustled the water-pumper out of its barn and rushed to the site. They were too late. Flames had engulfed the building and soon it burned to the ground. [1]

ck Sunday morning, Henry woke to cries of alarm. A fire at the factory! Volunteers hustled the water-pumper out of its barn and rushed to the site. They were too late. Flames had engulfed the building and soon it burned to the ground. [1]