Sufferers’ Land

The Episcopal Church in Norwalk

by Dave Barton

As with everything else in the early days of the village of Norwalk, Platt and Sally Benedict were involved in the religious life of the community. Although they were not baptized when they arrived, they saw the need for a church in Norwalk, and decided to establish one.

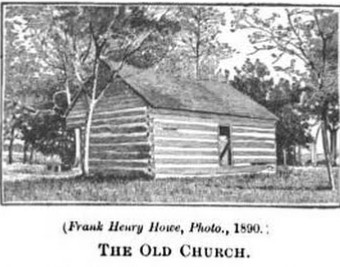

From Historical Collections of Ohio, Volume II, page 369.

In 1818, they hosted the first Episcopal service in their cabin, consisting of the reading of the Episcopal Church service, and a sermon by a layman. These lay meetings continued for years, first in private homes, and later in the Court House.

In 1820, Platt and Sally organized the first Sabbath School in the Court House. Most of the children of the town attended this non-denominational school. It would be years before a minister arrived in the village, but in the meantime, thanks to Platt and Sally’s initiative, a vibrant religious community developed.

Sunday, January 20, 1821, a minister named Reverend Searle visited the village for the first time and called a meeting to organize a new parish. Seventeen men attended, with Platt, of course, taking the lead. They decided to call the new parish, Saint Paul’s, and elected wardens and vestrymen. They elected Platt vestryman, and selected him to be a representative of the new parish to the fourth annual Diocesan Convention.

Reverend Searle could not stay in the parish, so he selected lay readers to carry out services in his absence. Platt, as usual, was one of those selected. Services continued every Sunday, with Reverend Searle occasionally attending to give Holy Communion and perform baptisms. The Bishop also visited the parish from time to time, so often that Sally’s son David ran away from home once because he was tired of polishing the bishop’s boots. [1]

During one visit, Sunday, February 17, 1822, Reverend Searle baptized Platt Benedict into the church. The next day, he held a meeting of the vestry in the Benedict home. He selected Rufus Murray to perform divine service in the parish once he became qualified. Reverend Searle continued to visit St. Paul’s parish occasionally, his last visit coming in 1826. [2]

During this time, a deacon by the name of S.A. Bronson also served the parish. He later recalled the religious life in Norwalk at the time. My first visit to this place was in 1825, to supply as far as a layman could, the place of a clergyman. No settled minister of any name had ever resided here, and only the Episcopal Church had attempted to keep up regular services. When, subsequently, a clergyman did become resident here, the regularity of the services depended upon the established forms of religion, as conducted by laymen. Many of you, no doubt, remember the old white court house, and cousin Ami Keeler with his tin horn, with which he used to call the people to worship — a horn more truly spiritual than some of more recent date. [3]

By this time, the parish conducted weekly services and had a strong Sunday school program for the religious education of all the children of the village, not just those of families in the parish. If not for Sally and Platt Benedict, none of this would have happened.

Footnotes:

[1] Story of David Benedict running away from home is from the undated text of an address given by Eleanor Wickham to the Sally DeForest chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

[2] First religious services in Norwalk and the early history of St. Paul’s Parish are described in detail by C.E. Newman in The Firelands Pioneer, Sept. 1876, pp. 45-47. The establishment of the Sabbath School is described in the above article and in The Firelands Pioneer, June 1867, p. 84.

[3] “Address of Rev. S.A. Bronson, D.D.” The Firelands Pioneer, November 1859, p. 7.

Note: Mary L. Stewart of Norwalk, a parishioner at St.Paul’s Episcopal Church, kindly assisted with this post.

#

This post was first published on this blog in 2009.

#

Previous Post: Women’s Life on the Frontier

Next Post: Native Americans

#

Thanks for visiting! Share and like this post below, and on Facebook. Let me know what you think in the comments. I’d love to hear from you!

Filed under: Benedict, Episcopal Church, Keeler, Norwalk, Ohio, Ohio, Uncategorized | Tagged: Benedict Genealogy, David Benedict, Episcopal Church, Firelands History, Frontier Life, Keeler genealogy, Platt Benedict, Sally DeForest Benedict, St Paul's Episcopal Church Norwalk Ohio, Sufferers' Land History | 7 Comments »

Winter would arrive soon, and they needed to obtain enough food to last until spring. However, that took money, which after the expenses of land and travel was in short supply. To make up the shortfall, Platt took a job with a crew cutting a road between Norwalk and Milan. He earned sixty dollars which he used to buy enough pork for the family to make it through the winter. [1]

Winter would arrive soon, and they needed to obtain enough food to last until spring. However, that took money, which after the expenses of land and travel was in short supply. To make up the shortfall, Platt took a job with a crew cutting a road between Norwalk and Milan. He earned sixty dollars which he used to buy enough pork for the family to make it through the winter. [1] Heavy traffic choked the road in both directions. Immigrants crowded westward, many of them destitute from the disastrous summer of 1816. Some persons went in covered wagons — frequently a family consisting of father, mother and eight or nine small children, with perhaps one a babe at the breast — some on foot and some crowded together under the cover with kettles, gridirons, feather beds, crockery and the family Bible, Watts’ Psalms and Hymn Book and Webster’s spelling book. Others started in ox carts and trudged on foot at the rate of ten miles a day. Many of them were in a state of poverty and begged their way as they went. Some of them died before they reached their destination. Broken wagons and discarded belongings littered the sides of the road. [3]

Heavy traffic choked the road in both directions. Immigrants crowded westward, many of them destitute from the disastrous summer of 1816. Some persons went in covered wagons — frequently a family consisting of father, mother and eight or nine small children, with perhaps one a babe at the breast — some on foot and some crowded together under the cover with kettles, gridirons, feather beds, crockery and the family Bible, Watts’ Psalms and Hymn Book and Webster’s spelling book. Others started in ox carts and trudged on foot at the rate of ten miles a day. Many of them were in a state of poverty and begged their way as they went. Some of them died before they reached their destination. Broken wagons and discarded belongings littered the sides of the road. [3] Sally Benedict was thirty-nine years old; she would turn forty on the road to Ohio. Born in Wilton, Connecticut in 1777, Sally was the youngest child of David and Sarah De Forest. Her father was a soldier in the Revolution with the Ninth Regiment of the Connecticut Militia. He took part in the disastrous battles for New York in 1776, the year before Sally was born.

Sally Benedict was thirty-nine years old; she would turn forty on the road to Ohio. Born in Wilton, Connecticut in 1777, Sally was the youngest child of David and Sarah De Forest. Her father was a soldier in the Revolution with the Ninth Regiment of the Connecticut Militia. He took part in the disastrous battles for New York in 1776, the year before Sally was born. He had no trouble finding willing helpers; most settlers looked forward to assisting new neighbors. In later days, one of them would recall — When the pioneer had been swinging his axe for weeks, and maybe for months, together, it is often cheering to hear that there is to be a log raising in the neighborhood. He anticipates at once the pleasure that is to be derived from meeting his neighbors, and having with them a little social chat, or the exchange of a few sprightly jokes. [2]

He had no trouble finding willing helpers; most settlers looked forward to assisting new neighbors. In later days, one of them would recall — When the pioneer had been swinging his axe for weeks, and maybe for months, together, it is often cheering to hear that there is to be a log raising in the neighborhood. He anticipates at once the pleasure that is to be derived from meeting his neighbors, and having with them a little social chat, or the exchange of a few sprightly jokes. [2]