Sufferers’ Land

Last Reunion of the Pioneers

by Dave Barton

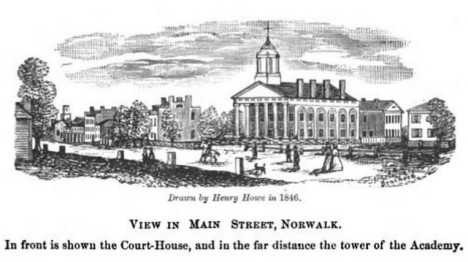

The Fourth of July 1857 was a Saturday. From all over Erie and Huron counties, people gathered for the reunion, an assembly of the early settlers and their descendants. The residents of Norwalk had prepared a celebration for the day, to include a sumptuous feast. [1]

Portrait of Eleutherous Cooke from Wikimedia Commons

The speaker for the occasion was former U.S. Congressman Eleutherous Cooke of Sandusky, a sixty-nine year old lawyer who had come to the Firelands in 1819. A painting of him shows a handsome, strong willed man. Clean-shaven, as was the custom of that time before the Civil War, he had a resolute set to his mouth, and a determined gaze. From his speech and his letters, it is easy to see that he was a gracious and well-mannered gentleman.

In addition to serving in Congress, he was a member of the Ohio House of Representatives for many years and obtained the first charter for a railroad in the United States.

People of that day expected eloquence and inspiration from their speakers — and Eleutherous Cooke was a master orator. He once made a speech to over forty-thousand people to commemorate the anniversary of the Battle of Fort Meigs. A contemporary account said that he had a wonderful command of the language, (and) was an orator very flowery and imaginative. Today we would say he was long-winded. However, in 1857, his audience appreciated his comments, especially because he took pains to praise their accomplishments.

His speech was grandiose in parts, but it also demonstrated a connection with the men and women he addressed. Eleutherous counted himself among the pioneers, a point he made several times during his speech. He knew personally of the trials his audience had endured and the successes they enjoyed. He understood them. [2]

On the platform with Eleutherous was another man who understood the people assembled in Norwalk that day — Platt Benedict. He knew Eleutherous Cooke from the days when Mr. Cooke came to Norwalk to argue cases before the County Court. [3]

This celebration would never have taken place if not for Platt Benedict. He must have smiled with pride when he heard Eleutherous say, “I am most happy to know — thanks to the excellent gentleman who first suggested the design — that a Historical Society has been formed, and I am now before you, in part, the selected organ of that society, to urge upon it, and upon all who approve its object, a searching and faithful fulfillment of its purpose.” [4]

Platt, and everyone else present, knew Eleutherous was referring to him. As in everything he was involved with, Platt had taken the lead. He was a leader in the settlement of the Firelands and had been involved in the political, social and economic development of the region.

As Eleutherous put it so eloquently, Platt had come “to build the cabin — to fence the crops — to open the roads — to lay out the towns and cities — to establish the schools for the education for the young, and to found the churches for worship of God.”

Platt had not only done all these things, he had been the leader in all these things. It only made sense that he should lead in preserving the heritage of the pioneers assembled here today — and the heritage of those who had already died.

Much of Eleutherous’ speech struck a chord in Platt’s memory. He told anecdotes of the early settlers’ trials and fears, successes and joys — some humorous to make his audience laugh, some tragic to make them weep.

Platt no doubt was moved when Eleutherous referred to “the little remnant of the old pioneers not yet fallen from around us but (whose) summer is past (whose) autumn has gone by.” Platt looked at the crowd and saw the faces of those he knew in younger days and recalled those who were no longer there — who could not participate in this celebration of their accomplishments.

“The images of the cherished dead,” Eleutherous said, “present themselves before me. In such a presence, how can I conceal the feelings of utter desolation that overwhelm me, when I remember that I am the sole survivor, save one, of a family circle of fourteen who sought with me this land for their home, and whose ashes now repose in the soil of the Firelands.”

This was Platt’s experience as well. He came to this village forty years before with a wife and five children. Now only his eldest daughter Clarissa survived. The rest of his family was gone, most having died young.

How long ago that time over forty years before must have seemed to Platt, and yet so near. He came to this land seeking opportunity, for himself and his family. He achieved much — all his dreams came true.

At the close of his speech, The Honorable Eleutherous Cooke addressed the children and grandchildren of the pioneers. “You are now in the full possession of this priceless heritage,” he told them. “You need not be reminded of its cost. Its title was written by the point of the sword in the blood of our fathers — it was enriched and perfected by their toils and labors.”

Then Eleutherous challenged the younger members of the audience. “The great trust is in your hands. Let the solemn obligation it imposes sink deep into your hearts; and, as the old friend and associate of your fathers, seizing this last occasion to impart my counsel, let me charge you, as the heaven-allotted sentinels of your country — as the champions of her honor and the defenders of her liberties, to guard with eternal vigilance, this sacred deposit — to shield it alike from the assaults of the foreign foe and the mal-administration of the domestic enemy; and to hand it down unfettered, unencumbered, inviolate and unstained to your children, bright in all that beauty and splendor which ushered in the Glory of its first Morning upon the World!” [5]

Little did Eleutherous Cooke, or Platt Benedict or any of the people assembled there that day know how great a challenge the children and grandchildren of the pioneers would face. A storm was gathering. Soon it would consume the entire nation in a great and terrible war — a war that would reach into the villages and farms of the Firelands and change the lives of all.

The children and grandchildren of the settlers of the Firelands would face a challenge that no one could imagine on that Independence Day, 1857. They would create a new heritage that would match — and eclipse — the heritage of the pioneers.

The End

Footnotes:

[1] Description of the Reunion of the Pioneers is from The Firelands Pioneer, New Series, Volume I, Number 1; The Firelands Historical Society; June 1858; p. 30.

[2] Information about Eleutheros Cooke is from multiple internet sources: COOKE, Eleutheros – Biographical Information, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-Present; Cooke House, Ohio Historical Society Website; and Eleutheros Cooke Collection at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center. A portrait of Representative Cooke is at the Ohio Memory website.

[3] From The Firelands Pioneer, New Series, Volume I, Number 1; The Firelands Historical Society; June 1858; p. 25.

[4] This quote from Mr. Cooke’s speech is from The Firelands Pioneer, New Series, Volume I, Number 1; The Firelands Historical Society; June 1858; p. 9.

[5] Excerpts from the conclusion of Mr. Cooke’s speech are from The Firelands Pioneer, New Series, Volume I, Number 1; The Firelands Historical Society; June 1858; p. 12.

#

This post was first published on this blog in 2009.

#

Previous Post: Pioneer Heritage

#

Thanks for visiting! Share and like this post below, and on Facebook. Let me know what you think in the comments. I’d love to hear from you!

Filed under: Benedict, Norwalk, Ohio, Ohio, Uncategorized | Tagged: Eleutheros_Cooke, Firelands Historical Society, Firelands History, Heritage of the Pioneers, Norwalk Ohio History, Ohio History, Platt Benedict, Reunion of Pioneers 1857, Sufferers' Land History, US House of Representatives | 6 Comments »