Sufferers’ Land

Future Warriors of Norwalk

by Dave Barton

Dave Benedict was at Kenyon College during the Cholera epidemic of 1854. Some of the grandchildren of the pioneers were able to attend college, and Dave was one of the first to go.

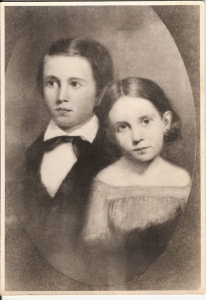

David Deforest Benedict as a young man

Dave was popular and very active on campus. He helped start a fraternity, founded and was the first editor of The Collegian, the college’s first monthly magazine, and also started Kenyon’s annual, which was the third such publication in the country. [1]

Fanny Benedict still lived at home. Dave visited her and his relatives often, and it was probably during one of these visits that he met a young woman from New Haven Township, Harriott Melvina Deaver.

Harriott Deaver was born in Watertown, New York on May 4, 1835. Later in life, she told of seeing rafts of logs from the North Woods floating down the river and going end-over-end over the falls. She moved to New Haven Township in Huron County with her parents when she was five years old. At that time, New Haven was a busy town, a way station for wagons carrying grain to Milan. In later years, she remembered the wagons going past her house, drawn by horses with tinkling bells.

Harriott was educated in Cuyahoga Falls, where she learned French. She was a dignified woman, who stood erect and solidly on her heels, feet pointed straight ahead. That trait and her features made some wonder if she was descended from Native Americans. [2]

Harriott’s father James Deaver was a cabinetmaker. He was a man of modest means with a net worth of $1,200. In 1850, the Deaver household consisted of ten people — James Deaver, age sixty-five, his wife Harriott, fifty-five, one son and six daughters, of whom Harriott was the youngest. As was customary for a family of their means, a German woman named Margret Singer lived with them and helped Harriott’s mother with the chores. [3]

The Deaver’s son Oscar was crippled. He had lost both hands while attempting to push a friend from in front of a cannon on the Fourth of July several years earlier.

James Deaver was originally from Maryland, where he was born in 1782 as James Devier, his family having come to America from France. His parents died when he was young. Relatives raised him and changed his name to Deaver. In 1808, he married Harriott Shaon, the daughter of David and Eleanor Shaon, who were slaveholders in Maryland.

James and Harriott had their first child Ellen in 1808. Harriott’s mother presented the child with an African American girl for a body servant. James, who did not believe in slavery, was disgusted and moved his family to New York to get away from the institution. He took the girl with him and freed her when they arrived. [4]

Dave Benedict graduated from Kenyon in 1856 and in October he and Harriott married. They moved to Cleveland, where he attended Case Medical College. He was a sociable man. While at Case, he met a young man who would play a large role in his life and the life of his descendants, Louis Severance.

Louis was born in Cleveland on August 1, 1838 to Solomon and Mary Long Severance. Louis never knew his father, who died before he was born. After Solomon died, Louis’ mother moved in with her father, David Long, Jr., who was the first medical doctor in town, and founded the Academy of Medicine of Cleveland.

Louis attended Cleveland Public schools, and when he graduated in 1856, he went to work at the Commercial Bank of Cleveland. Louis may have met Dave Benedict at his grandfather’s house, or perhaps at church, both men being Episcopalians. Dave was twenty-three and Louis was eighteen when they met, but in spite of the difference in age and background, they became good friends.

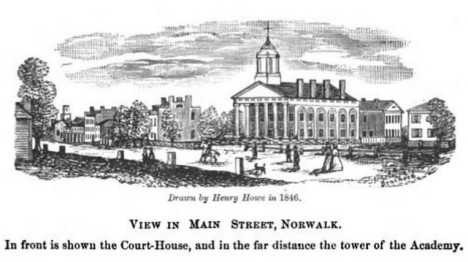

Dave took Louis to Norwalk to visit his family, and introduced him to his sister Fanny. Fanny was seventeen at the time, and liked the looks of this young bank employee from Cleveland. The feeling was mutual, and Louis started to court her. [5]

The oldest Wickham son also left Norwalk to go to college.

Charles Wickham as a young man. Clipped from family photo.

Charlie Wickham began studying law at Cincinnati Law School in 1854. Before leaving for college, he worked in the family business. He started at the Norwalk Reflector as a delivery boy when he was very young. He later remembered delivering the newspaper on New Year’s Day 1852 announcing the beginning of railroad service to Norwalk. [6]

Charlie remembered those days working at the newspaper fondly. In later years he remarked, I look upon the Reflector Office as my alma mater, from whence I have drawn, in great part, my sustenance, both physical and intellectual. At its reading table I received my first idea and knowledge of this world – its lights and shades – its follies and crimes – its men and women: indeed, of everything that I know; for at the editor’s table you may learn of everything and everybody – love and law – religion and reason – politics and politeness – statesmen and scholars – poets and professors – merchants and mechanics. There is hardly a limit to the knowledge which you may there obtain; it is a “Pierean Spring,” whose waters never fail. Author and statesman, philosopher and president, have breathed with the air of a printing office, an inspiration, and have gone forth to electrify and govern the world. [7]

Charlie’s high school sweetheart Emma Wildman also went off to college, a rarity for women in those days. After graduating from high school, she attended Oberlin College. [8] Oberlin was one of the first co-educational schools in the United States, accepting women in 1837.

The world was changing for this new generation, the grandsons and granddaughters of the pioneers. The struggles and hardships of the early settlers had created for these young people an opportunity unparalleled in the nation’s history. The pioneers’ grandchildren were proud of what those hardy people had accomplished, and would be active in preserving their heritage. Like their grandparents, they also would be tested, not by struggles and hardships of the frontier, but on the battlefield.

Footnotes:

[1] Story of David Benedict’s life and accomplishments at Kenyon College are from Family, by Ian Frazier, Farrar, Straus Giroux; 1994; p. 82.

[2] The early life of Harriott Benedict is from the Family History: Wickham, Benedict, Preston & Deaver, (unpublished) by Agnes and Harriott Wickham, edited by Dave Barton; p. 10.

[3] Information about the Deaver family in New Haven Township is from The 1850 Huron County Census, pp. 192b & 193a.

[4] Information about the Deaver family history is from the Family History: Wickham, Benedict, Preston & Deaver, (unpublished) by Agnes and Harriott Wickham, edited by Dave Barton; pp. 9-10.

[5] Information about Louis Severance is from the American National Biography, Volume 19, p 662. Information about his grandfather, Dr. David Long is from The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

[6] “When the ‘Iron Colt’ First Dashed into Norwalk,” The Firelands Pioneer, New Series, Volume XX; The Firelands Historical Society; December, 1918; p. 2065.

[7] “History of the Firelands Press,” by C.P. Wickham, The Firelands Pioneer, Old Series, Volume II, Number 4; The Firelands Historical Society; September 1861, p. 12.

[8] From Obituaries – The Fireland Pioneer, New Series, Volume XXI; The Firelands Historical Society; January 1920, p. 2486.

#

This post was first published on this blog in 2009.

#

Previous Post: Railroads and Cholera

Next Post: Pioneer Heritage

#

Thanks for visiting! Share and like this post below, and on Facebook. Let me know what you think in the comments. I’d love to hear from you!

Filed under: Benedict, Civil War, Deaver, DeForest, Norwalk, Ohio, Ohio, Severance, Uncategorized, Wickham, Wildman | Tagged: Benedict Genealogy, Charles Preston Wickham, Civil War, David DeForest Benedict, Deaver Genealogy, Fanny Benedict, Firelands History, Harriott Deaver, James Deaver, Louis Severance, Severance Genealogy, Sufferers' Land History, Wickham Genealogy | 7 Comments »